—-Scroll down to read the German and French version—-

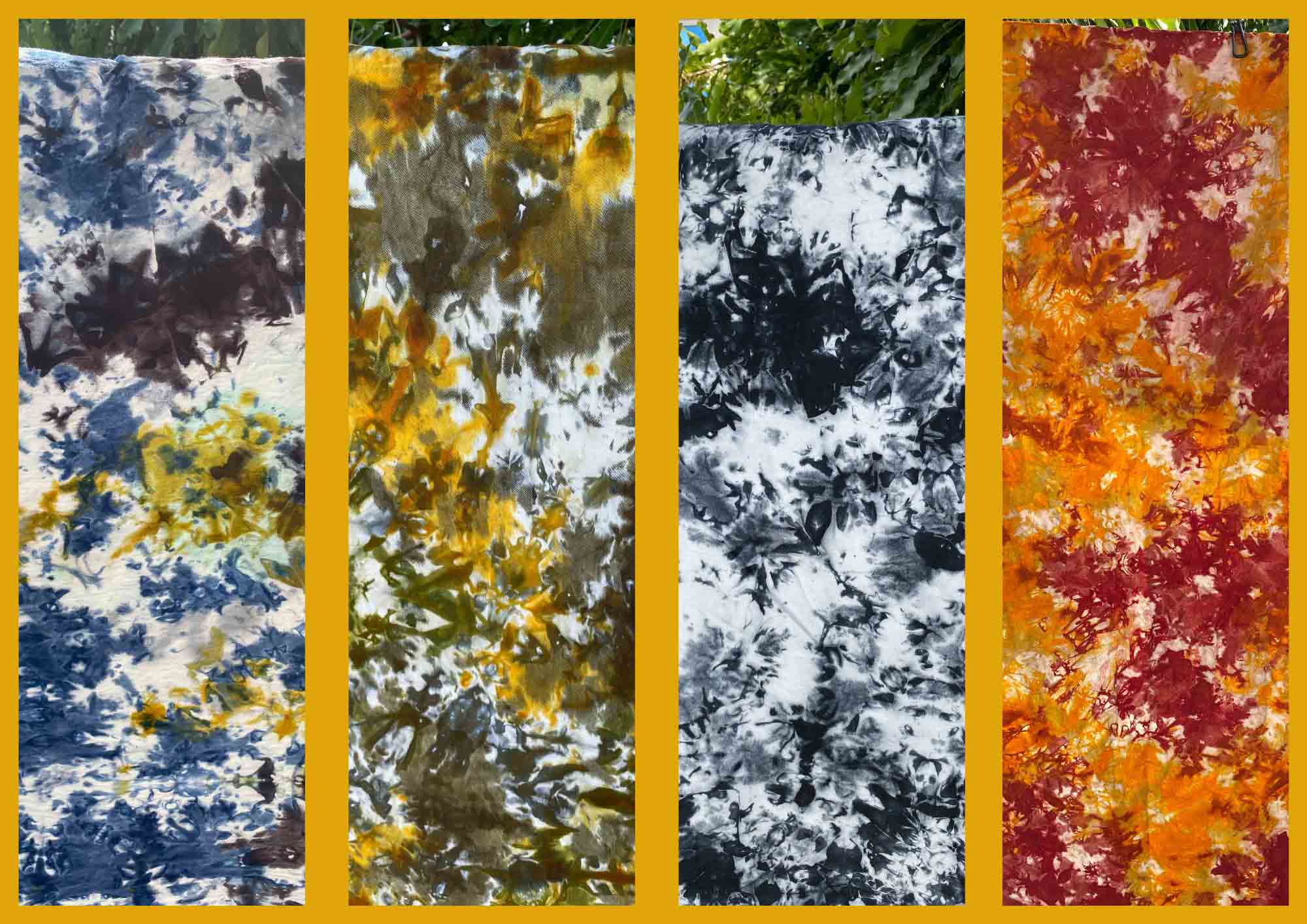

In the summer of 2024, something unprecedented was created in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso: 100 metres of hand-batiked Kokodunda, developed for the Berlin fashion brand Kaya and the planned Elements collection, were to be dyed in four patterns: Air, Fire, Earth and Water.

What sounded like a clear task quickly turned out to be a complex, deeply human and artisanal adventure – spanning continents, cultures, temperatures and very different production logics.

For Diallo tissue tales, it is precisely this space between worlds that is central: where materials, knowledge and people come together without simplifying each other. This project was not outsourcing, but a dialogue on equal terms – and thus a living example of culture-connecting work.

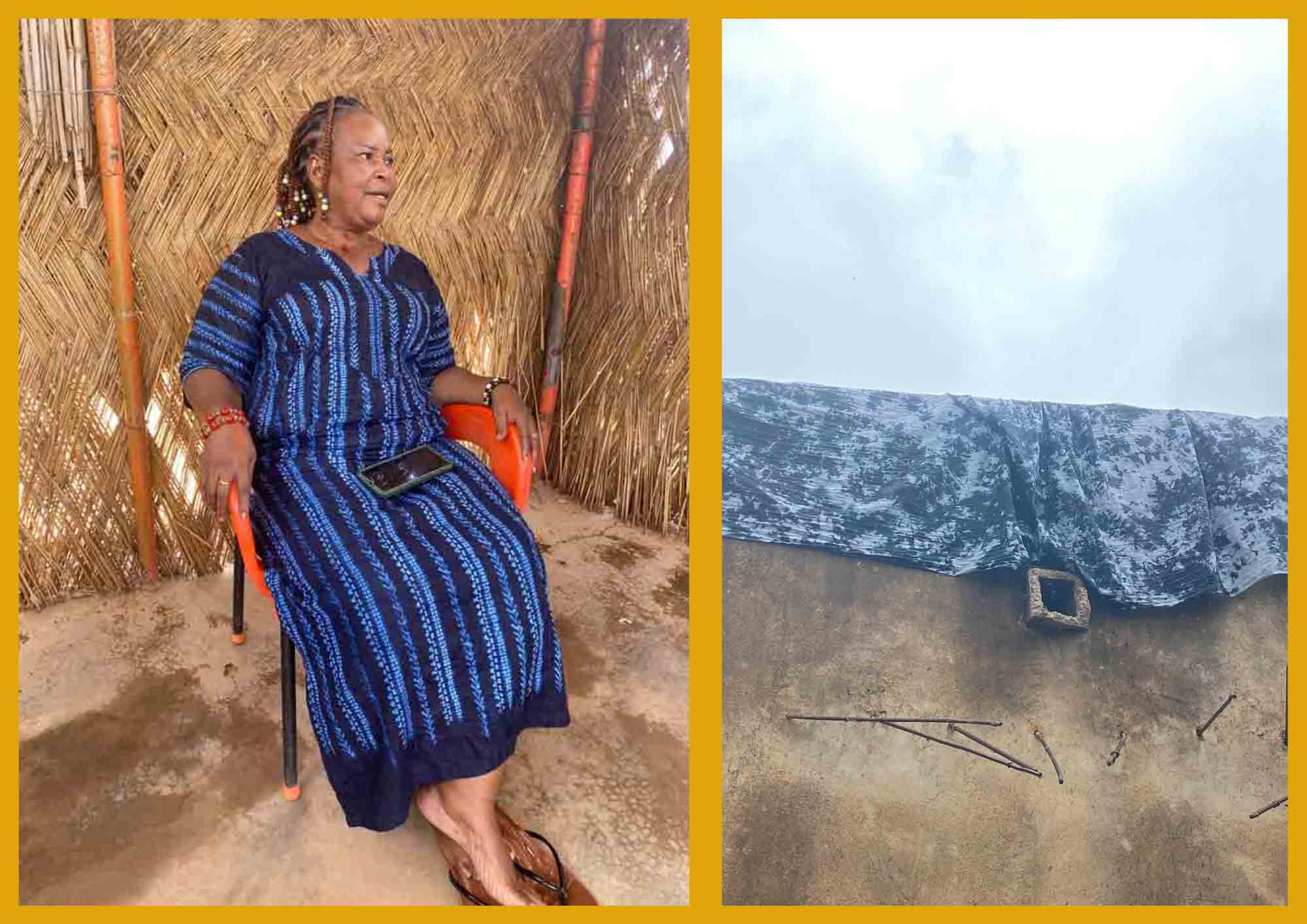

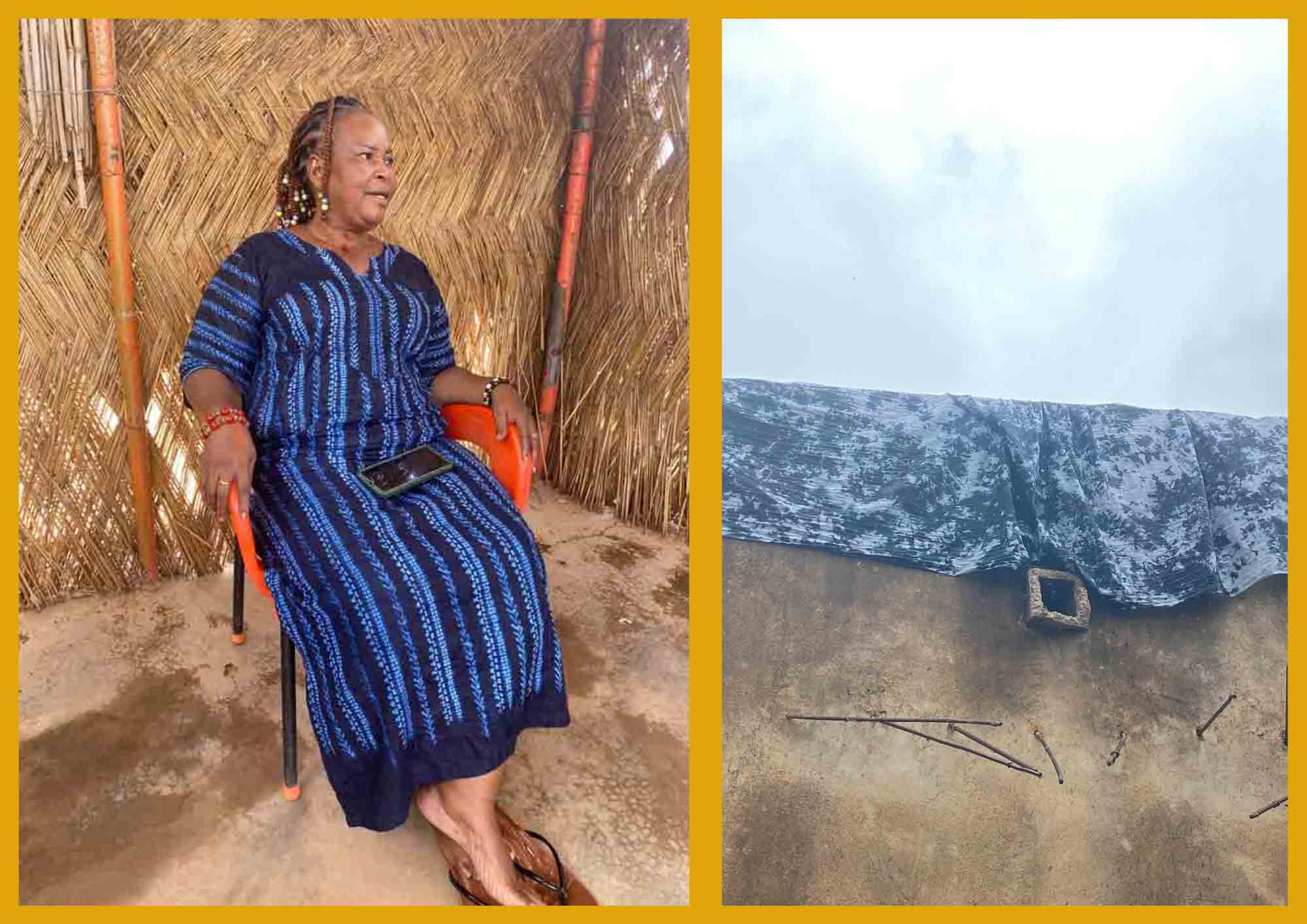

Armande Yaméogo, the artistic director of the project

Together with my partner Armande Yaméogo, founder of the Wobisi association, I tested, developed and adapted these patterns. We dyed, discarded, rethought and dyed again until the founder of KAYA, Ashley Jones, could really resonate with the patterns. Much of it was truly pioneering work.

When craftsmanship actually wants unique pieces

Kokodunda is a traditional fabric. It thrives on the uniqueness of the play of colours on the fabric. Normally, batik dyeing produces a single cloth – with exactly that one moment, that one movement, that one mixture of colour, water, heat and intuition. That is precisely what makes it so beautiful.

However, the Kaya label wanted something different: four designs that could be repeated and produced in small series. Not identical – but with the same expressiveness, the same energy, the same depth.

That was the biggest challenge of this project. Because for each re-dyeing, it meant:

- Re-mixing colours and fixatives in exactly the same quantities

- Re-evaluating water quality and temperature again and again

- Comparing fabric qualities, in the traditional way with the aid of scales for large quantities of fabric

- Keeping patterns deliberately similar yet vibrant

We learned that:

Reproducibility in handicrafts has nothing to do with copying.

All factors must be translated from a single fabric to several metres. There are a number of unknowns, especially when it comes to sourcing: how are the colour powders on the market put together, and what fabric quality does the dealer have in stock or can he procure in advance from a neighbouring country?

Fortunately, Ashley Jones is familiar with the conditions in West Africa and approached us with a great deal of understanding for all the adversities. This, too, is part of fair and respectful cooperation.

Not all yard goods are created equal

Fabric energy: Tanja & Armande

In Burkina Faso, cotton fabric can be produced in two ways:

- As coupons, industrially manufactured, imported from neighbouring countries such as Niger or China

- In local weaving centres, hand-woven, high-quality, but also correspondingly expensive

For the Elements project, we had to make a conscious decision to use industrially manufactured cotton. Not because it is ‘better’ – but because it takes on colours more evenly and brilliantly. The hand-woven fabrics are beautiful, but they react very individually, which makes them even less predictable for serial dyeing.

That was also a learning curve:

Quality is not only evident in the material, but also in the interplay between material and technique.

The joy when a test dyeing works

The fun after hard work

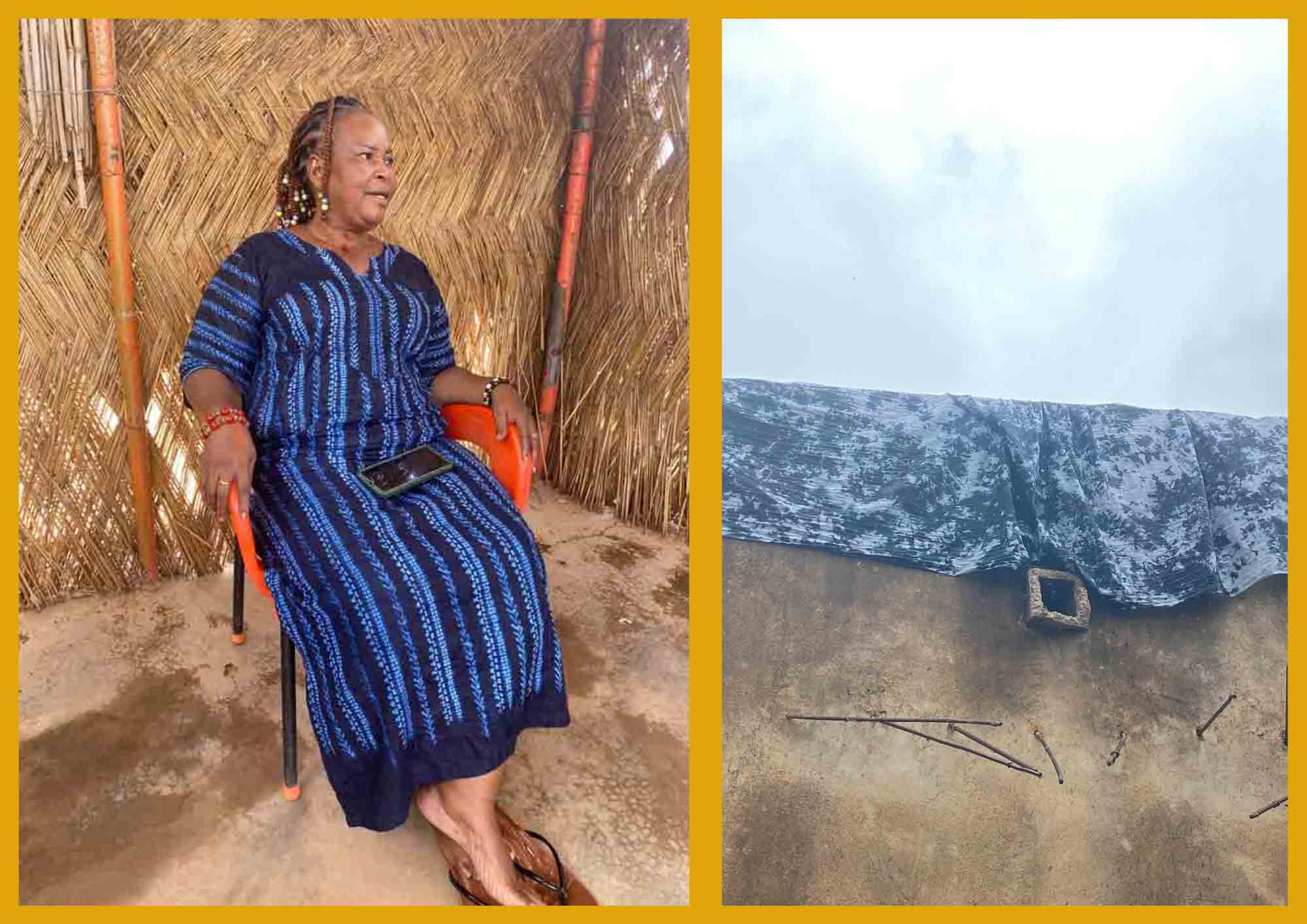

There were many moments of doubt. And then there were those other moments: when a new test dyeing came out of the water, dried in the hot Sahel sun – and suddenly everything was right: colours, depth, rhythm.

This joy was particularly palpable during the tests for a later artistic collection by Ashley Jones. Every time a fabric said ‘yes’, there was laughter, applause and photography.

And as we bent over, applying the boiling hot dye to the wet fabric panels, washing them out and spreading them out to dry on roofs and railings, someone would always call out: ‘Ashley!’ Because Armande’s granddaughter, who helped with the dyeing, is also called Ashley. So her name echoed through the house and yard, was called out, laughed at, called out again – and incidentally became the soundtrack to this project.

What remains

At the end of this intense August 2024, there was much more than just fabric:

- a recipe card with precise details of the mixing ratios of the dyes, fixatives and information on fabric quantity and quality for future orders

- valuable experience for the production processes of Diallo tissue tales

- the material for a future artistic collection by Ashley Jones

- and above all: a large order for Armande and her association

Armande told me that Wobisi had never earned such a large sum from a single order before. This money will now go directly towards supporting her children and grandchildren.

This is how West African handicrafts are given a platform in Berlin – and Diallo tissue tales remains what it wants to be: a space for encounters, translation and shared value creation.

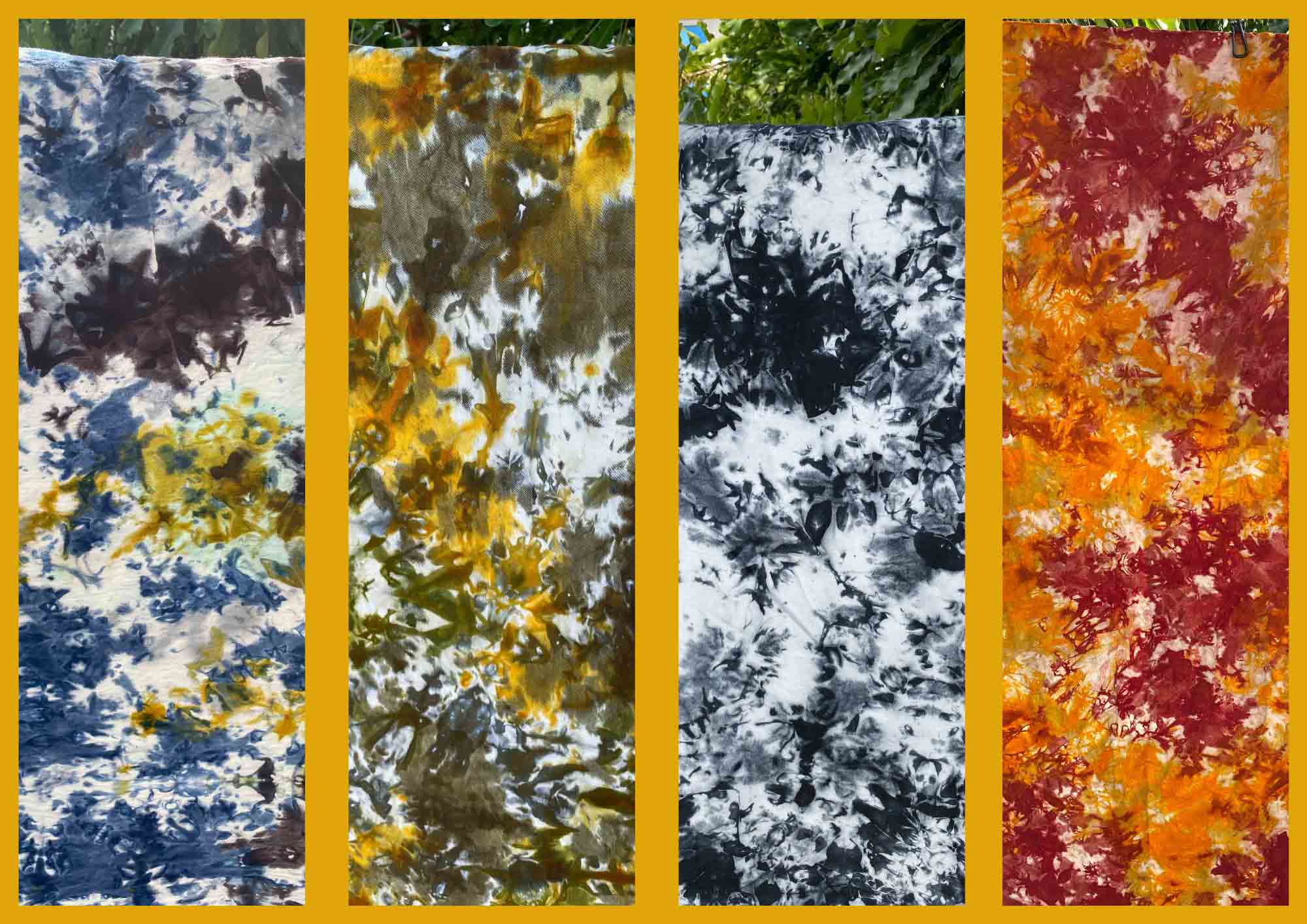

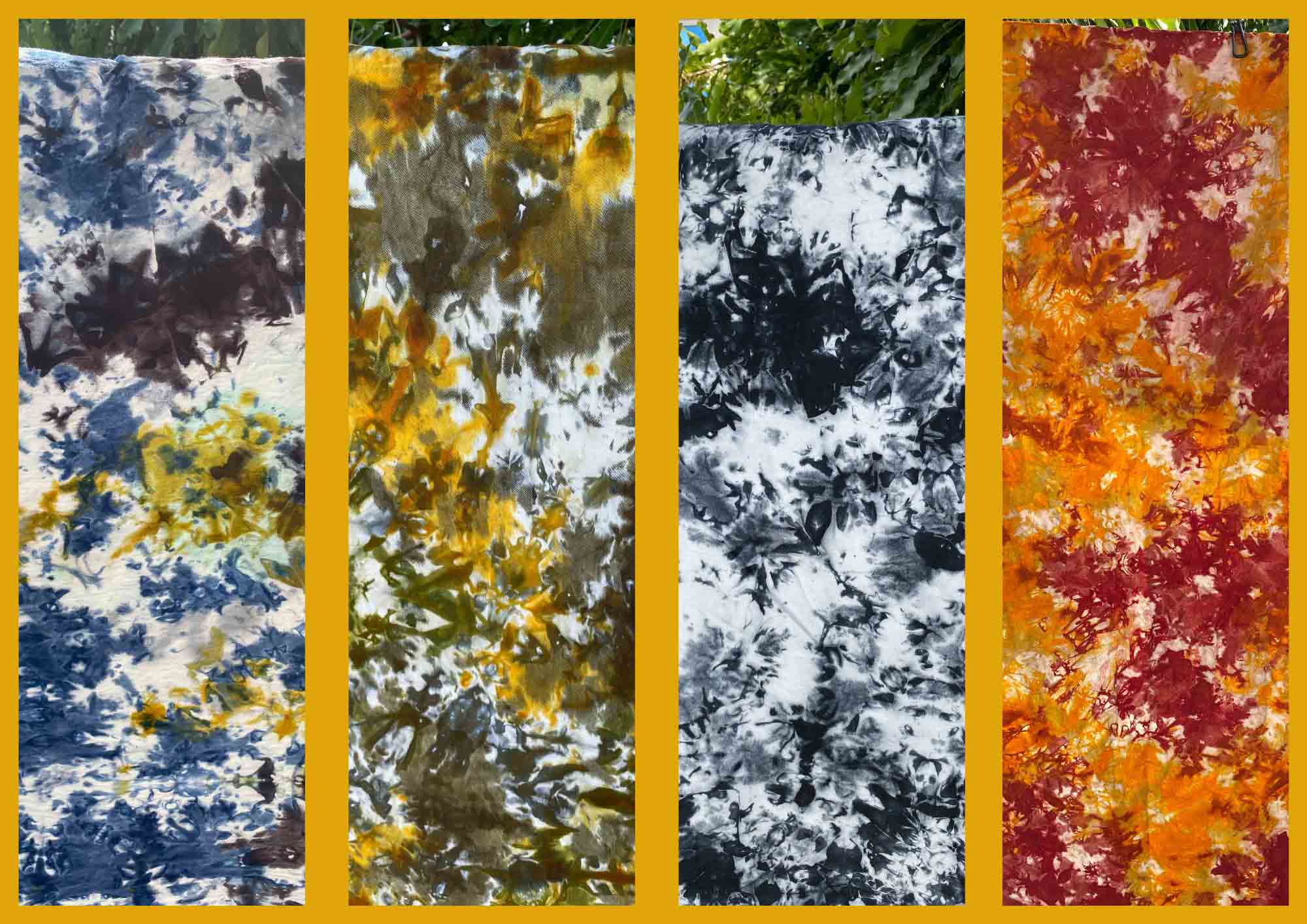

All elements: water, earth, air & fire

What happens next

As soon as the Kaya Elements collection is out in the world, the next blog post will follow here, of course. We will also keep you up to date on all social media channels.

📸 The making-of this project will also be followed up – because these stories of culture-connecting projects need to be told.

———————————

100 Meter Pionierarbeit

Wie Kokodunda aus Ouagadougou seinen Weg nach Berlin fand

Im Sommer 2024 entstand in Ouagadougou, der Hauptstadt von Burkina Faso, etwas, das es so noch nicht gegeben hatte: 100 Meter handgebatikter Kokodunda, entwickelt für die Berliner Fashion-Marke Kaya und die geplante Elemente-Kollektion sollten vier Muster gefärbt werden: Air, Fire, Earth und Water.

Was nach einer klaren Aufgabenstellung klingt, entpuppte sich schnell als ein komplexes, zutiefst menschliches und handwerkliches Abenteuer – zwischen Kontinenten, Kulturen, Temperaturen und sehr unterschiedlichen Produktionslogiken.

Für Diallo tissue tales ist genau dieser Raum zwischen den Welten zentral: Dort, wo Materialien, Wissen und Menschen aufeinandertreffen, ohne sich gegenseitig zu vereinfachen. Dieses Projekt war kein Outsourcing, sondern ein Dialog auf Augenhöhe – und damit gelebte kulturverbindende Arbeit.

Armande Yaméogo, the artistic director of the project

Gemeinsam mit meiner Partnerin Armande Yaméogo, Gründerin des Vereins Wobisi, habe ich diese Muster getestet, entwickelt und adaptiert. Wir haben gefärbt, verworfen, neu gedacht und wieder gefärbt, bis die Gründerin von KAYA, Ashley Jones, mit den Mustern wirklich in Resonanz gehen konnte. Vieles davon war echte Pionierarbeit.

Wenn Handwerk eigentlich Unikate will

Kokodunda ist ein traditioneller Stoff. Er lebt von der Einmaligkeit des Farbspiels auf dem Gewebe. Normalerweise entsteht beim Batikfärben ein einzelnes Tuch – mit genau diesem einen Moment, dieser einen Bewegung, dieser einen Mischung aus Farbe, Wasser, Hitze und Intuition. Genau das macht seine Schönheit aus.

Für das Label Kaya war jedoch etwas anderes gefragt: Vier Designs, die wiederholbar sind und in kleinen Serien gefertigt werden können. Nicht identisch – aber mit derselben Aussagekraft, derselben Energie, derselben Tiefe.

Das war die größte Herausforderung dieses Projekts. Denn für jede Nachfärbung hieß es:

- Farben und Fixierung in exakt gleichen Menge neu anzusetzen

- Wasserqualität und -temperatur immer wieder neu einzuschätzen

- Stoffqualitäten zu vergleichen, bei großen Stoffmengen ganz klassisch mit Hilfe einer Waage

- Muster bewusst ähnlich und doch lebendig zu halten

Wir haben gelernt:

Reproduzierbarkeit im Kunsthandwerk hat mit Kopieren nichts zu tun.

Alle Faktoren müssen vom Einzelstoff auf mehrere Meter übersetzt werden. Dabei gibt es eine Reihe von Unbekannten, die vor allem beim Sourcing entstehen: Wie werden die Farbpulver auf dem Markt zusammengestellt, und welche Stoffqualität hat der Händler auf Lager bzw., welche kann er mit Vorlauf in einem Nachbarland beschaffen.

Glücklicherweise ist Ashley Jones mit den Gegebenheiten in Westafrika vertraut und begegnete uns mit viel Verständnis für alle Widrigkeiten. Auch das ist Teil einer fairen, respektvollen Zusammenarbeit.

Meterware ist nicht gleich Meterware

Fabric energy: Tanja & Armande

In Burkina Faso kann Baumwollstoff auf zwei Arten entstehen:

- Als Coupon, industriell gefertigt, importiert aus Nachbarländern wie Niger oder aus China

- In heimischen Webzentren, handgewebt, hochwertig, aber auch entsprechend kostspielig

Für das Elemente-Projekt mussten wir uns bewusst für industriell gefertigte Baumwolle entscheiden. Nicht, weil sie „besser“ ist – sondern weil sie Farben gleichmäßiger und brillanter annimmt. Die handgewebten Stoffe sind wunderschön, aber sie reagieren sehr individuell, was für serielle Färbungen noch weniger kalkulierbar ist.

Auch das war eine Lernkurve:

Qualität zeigt sich nicht nur im Material, sondern im Zusammenspiel von Material und Technik.

Die Freude, wenn eine Probefärbung passt

The fun after hard work

Es gab viele Momente des Zweifelns. Und dann diese anderen Momente:

Wenn eine neue Probefärbung aus dem Wasser kam, in der heißen Sahel-Sonne trocknete – und plötzlich alles stimmte: Farben, Tiefe, Rhythmus.

Gerade bei den Tests für eine spätere künstlerische Kollektion von Ashley Jones war diese Freude spürbar. Jedes Mal, wenn ein Stoff „Ja“ sagte, wurde gelacht, geklatscht, fotografiert.

Und während wir vornübergebeugt die kochend heiße Farbe auf die nassen Stoffbahnen auftrugen, sie auswuschen und zum Trocknen auf Dächern und Geländern ausbreiteten, rief immer irgendjemand: „Ashley!“

Denn Armandes Enkeltochter, die beim Färben mithalf, heißt ebenfalls Ashley.

So hallte ihr Name durch Haus und Hof, wurde gerufen, gelacht, wieder gerufen – und wurde ganz nebenbei zum Soundtrack dieses Projekts.

Was geblieben ist

Am Ende dieses intensiven August 2024 stand weit mehr als Stoff:

- eine Rezeptkarte mit genauen Angaben zum Mischverhältnis der Farben, Fixierungen und Angaben zu Stoffmenge und -qualität für zukünftige Aufträge

- wertvolle Erfahrungen für die Produktionsprozesse von Diallo tissue tales

- das Material für eine künftige künstlerische Kollektion von Ashley Jones

- und vor allem: ein großer Auftrag für Armande und ihren Verein

Armande sagte mir, dass Wobisi noch nie zuvor eine so hohe Summe mit einem Auftrag verdient hat. Dieses Geld fließt nun direkt in das Leben ihrer Kinder und Enkelkinder.

So bekommt westafrikanisches Kunsthandwerk seine Bühne in Berlin –

und Diallo tissue tales bleibt das, was es sein will: ein Raum für Begegnung, Übersetzung und gemeinsame Wertschöpfung.

All elements: water, earth, air & fire

Wie es weitergeht

Sobald die Kaya-Elemente-Kollektion in der Welt ist, folgt hier natürlich der nächste Blogbeitrag. Auch auf allen Social-Media-Kanälen halten wir euch auf dem Laufenden.

📸 Das Making-of dieses Projekts wird ebenfalls weiter begleitet – denn diese Geschichten von kulturverbindenden Projekten müssen erzählt werden.

———————————

100 mètres de travail pionnier

Comment Kokodunda, originaire de Ouagadougou, a trouvé son chemin vers Berlin

Au cours de l’été 2024, quelque chose d’inédit a vu le jour à Ouagadougou, la capitale du Burkina Faso : 100 mètres de Kokodunda teint à la main, développé pour la marque de mode berlinoise Kaya et la collection Éléments prévue. Quatre motifs devaient être teints : Air, Feu, Terre et Eau.

Ce qui semblait être une tâche claire s’est rapidement révélé être une aventure complexe, profondément humaine et artisanale, entre continents, cultures, températures et logiques de production très différentes.

Pour Diallo tissue tales, c’est précisément cet espace entre les mondes qui est central : là où les matériaux, les connaissances et les personnes se rencontrent sans se simplifier mutuellement. Ce projet n’était pas une externalisation, mais un dialogue d’égal à égal – et donc un travail culturel concret.

Armande Yaméogo, the artistic director of the project

Avec ma partenaire Armande Yaméogo, fondatrice de l’association Wobisi, j’ai testé, développé et adapté ces motifs. Nous avons teint, rejeté, repensé et reteint jusqu’à ce que la fondatrice de KAYA, Ashley Jones, puisse vraiment entrer en résonance avec les motifs. Une grande partie de ce travail était véritablement pionnier.

Quand l’artisanat veut des pièces uniques

Le kokodunda est un tissu traditionnel. Il tire sa force de l’unicité des jeux de couleurs sur le tissu. Normalement, la teinture batik permet de créer un tissu unique, grâce à un moment précis, un mouvement précis, un mélange précis de couleur, d’eau, de chaleur et d’intuition. C’est précisément ce qui fait sa beauté.

Mais la marque Kaya avait une autre exigence : quatre motifs reproductibles et pouvant être fabriqués en petites séries. Pas identiques, mais avec la même force expressive, la même énergie, la même profondeur.

C’était le plus grand défi de ce projet. Car pour chaque nouvelle teinture, il fallait :

- Préparer à nouveau les couleurs et la fixation dans des quantités exactement identiques

- Réévaluer sans cesse la qualité et la température de l’eau

- Comparer les qualités des tissus, de manière classique à l’aide d’une balance pour les grandes quantités de tissu

- Veiller à ce que les motifs restent similaires tout en restant vivants

Nous avons appris que la reproductibilité dans l’artisanat d’art n’a rien à voir avec la copie.

Tous les facteurs doivent être transposés d’un tissu individuel à plusieurs mètres. Il existe toute une série d’inconnues, qui surviennent principalement lors de l’approvisionnement : comment les poudres de couleur sont-elles composées sur le marché, quelle est la qualité des tissus que le commerçant a en stock ou qu’il peut se procurer à l’avance dans un pays voisin ?

Heureusement, Ashley Jones connaît bien la situation en Afrique de l’Ouest et nous a accueillis avec beaucoup de compréhension pour toutes les difficultés. Cela fait également partie d’une coopération équitable et respectueuse.

Tous les tissus au mètre ne se valent pas

Fabric energy: Tanja & Armande

Au Burkina Faso, le coton peut être produit de deux manières :

- Sous forme de coupons, fabriqués industriellement, importés de pays voisins comme le Niger ou de Chine

- Dans des centres de tissage locaux, tissé à la main, de haute qualité, mais aussi plus coûteux

Pour le projet Elemente, nous avons dû opter délibérément pour du coton fabriqué industriellement. Non pas parce qu’il est « meilleur », mais parce qu’il prend des couleurs plus uniformes et plus brillantes. Les tissus tissés à la main sont magnifiques, mais ils réagissent de manière très individuelle, ce qui est encore moins prévisible pour les teintures en série.

Cela aussi a été un apprentissage: la qualité ne se manifeste pas seulement dans le matériau, mais aussi dans l’interaction entre le matériau et la technique.

La joie quand un échantillon de teinture convient

The fun after hard work

Il y a eu de nombreux moments de doute. Et puis d’autres moments :

quand un nouvel échantillon de teinture sortait de l’eau, séchait sous le soleil brûlant du Sahel et que soudain, tout était parfait : les couleurs, la profondeur, le rythme.

Cette joie était particulièrement palpable lors des tests pour une future collection artistique d’Ashley Jones. Chaque fois qu’un tissu disait « oui », on riait, on applaudissait, on prenait des photos.

Et tandis que nous étions penchés en avant pour appliquer la teinture brûlante sur les bandes de tissu humides, les rincer et les étaler sur les toits et les balustrades pour les faire sécher, quelqu’un criait toujours : « Ashley ! »

Car la petite-fille d’Armande, qui aidait à la teinture, s’appelle également Ashley.

Son nom résonnait ainsi dans toute la maison et la cour, était crié, suivi de rires, puis crié à nouveau, devenant ainsi la bande-son de ce projet.

Ce qui reste

À la fin de ce mois d’août 2024 intense, il restait bien plus que du tissu :

- une fiche recette avec des informations précises sur les proportions des couleurs, les fixations et des indications sur la quantité et la qualité du tissu pour les futures commandes

- une expérience précieuse pour les processus de production de Diallo tissue tales

- le matériel pour une future collection artistique d’Ashley Jones

- et surtout : une grosse commande pour Armande et son association

Armande m’a dit que Wobisi n’avait jamais gagné autant d’argent avec une seule commande. Cet argent est désormais directement investi dans la vie de ses enfants et petits-enfants.

C’est ainsi que l’artisanat ouest-africain trouve sa place à Berlin et Diallo tissue tales reste ce qu’il veut être : un espace de rencontre, de traduction et de création de valeur commune.

All elements: water, earth, air & fire

La suite

Dès que la collection Kaya-Elemente sera disponible, nous publierons bien sûr un nouvel article sur notre blog. Nous vous tiendrons également informés sur tous nos réseaux sociaux.

📸 Le making-of de ce projet sera également suivi, car ces histoires de projets culturels fédérateurs doivent être racontées.

———————————